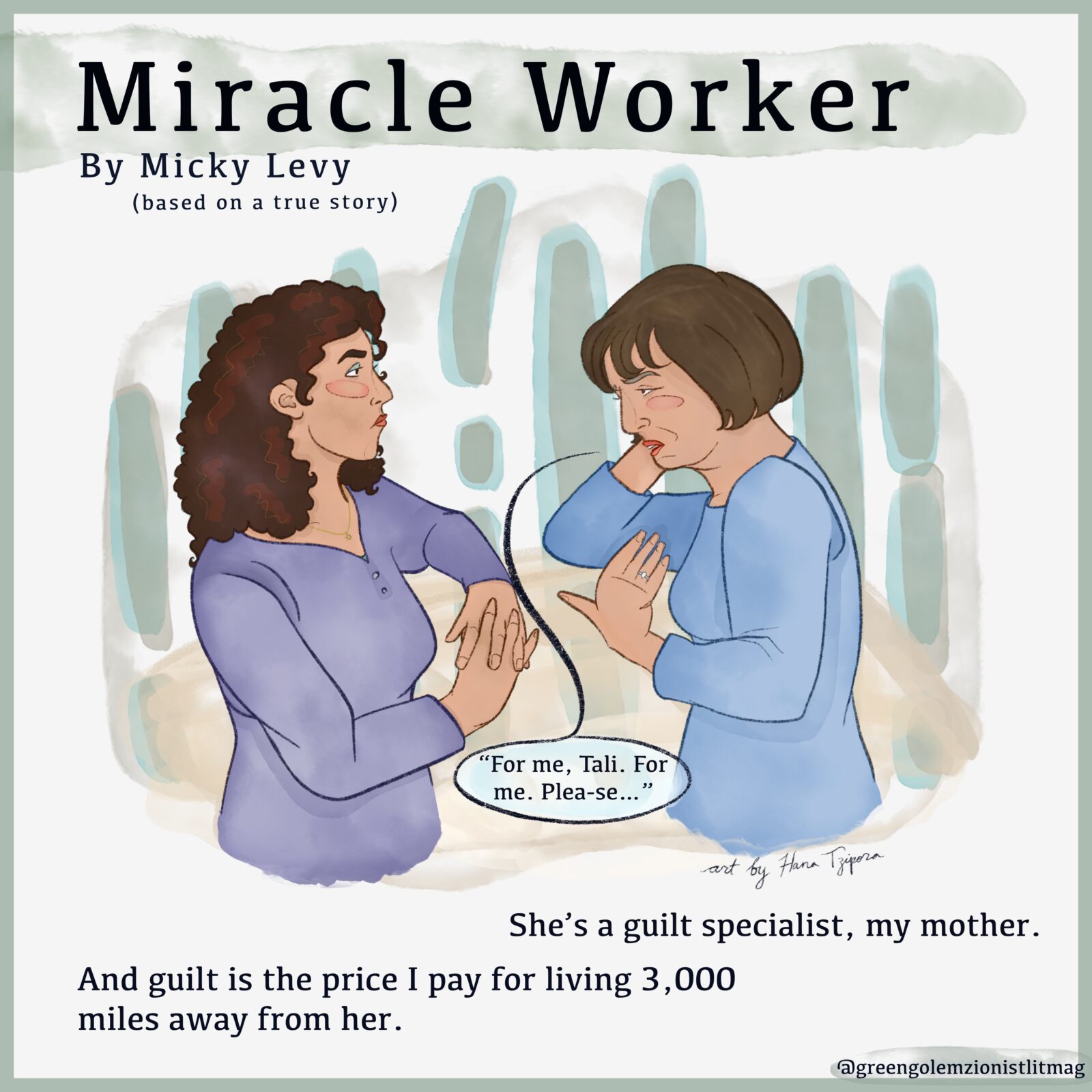

Miracle Worker

Micky Levy is a writer and filmmaker. She was born…

“For me, Tali. For me. Plea-se…” She’s a guilt specialist, my mother. And guilt is the price I pay for living 3000 miles away from her.

I’m thirty-three years old. By now, I should’ve been famous or given her grandchildren. She can name dozens, hundreds, of hopeful Israelis who took a flight to America and found fame and fortune within months. Weeks. Days! Only I, her daughter, am struggling after fifteen years. And the talent I have! And what a beauty I am! If I had a husband, I could blame my professional failure on a satisfying personal life. If I were booking roles in film and TV, I could blame my singlehood on a booming career. But I don’t have a husband, or even a boyfriend, and I don’t have a career. I can only blame myself.

I visit her once a year for two weeks, but usually, after a few days, I’m ready to return to my studio apartment in the Valley where her disappointed gaze can’t reach me. This visit is no different. On my third day in Israel, her inquiry begins. She eyes me for a long moment and finally says, “What’s that on your face, Tali?”

“What?”

“Is that a moustache?”

“I don’t have a moustache.”

“It’s staring right at me. Go look.”

“I don’t have a moustache!!” I shriek and march to the bathroom. I flick on the light and scrutinize my nonexistent facial hair in the mirror. She approaches, panther-like. “Maybe that’s why you’re not in the movies.”

“Yes, it’s my giant moustache.”

“Are you at least seeing someone?” She asks, massaging my shoulders.

“I don’t want to talk about it.” I gently push her away and storm out. She stalks me to the living room. “Don’t be mad, Tali. Don’t be mad… I’m trying to help you. I heard of someone, a special man. He’ll touch your head, and all your problems will disappear,” she says matter-of-factly and with a straight face.

“I don’t have problems. I like my life,” I tell her, but I wonder if that’s true. Most days, I’m lonely. And I’ve been working at Pete’s House of Ribs for so long that the manager has offered to train me to be his replacement when he retires.

“His name is Rabbi Nissim. You might have heard of him,” she continues in a sweet voice, feigning oblivion to my obvious despair. “He’s a rising star in orthodox Israeli radio.”

“I don’t listen to Israeli radio.”

“Rabbi Nissim is renowned. Everybody knows him,” she insists.

She does this every time I visit. Her strategy is simple but effective: She mentions the miracle worker du jour casually, off-handedly, then she keeps talking about them, swearing on everything holy that they’ll reveal my future to me, identify what I’m doing wrong and exorcise the bad jujus from my energy until, under incredible duress, I agree to meet with them. The meetings are forgettable, often unpleasant and leave me depressed and decidedly unaltered. Like the time she took me to a psychic in Haifa with six cats and a mullet, who diagnosed me with an evil eye of the third-degree and concocted a costly spell that involved a foul-smelling, loose ointment into which, I’m sure, her cats had peed. Miracle workers du jour charge a hefty fee, but my mother, a believer in all-things-fantastic, never hesitates to pay it.

This time, I’m determined to resist. Mother is equally determined. “I just know Rabbi Nissim can fix you,” she says as if I were a leaky faucet. But I am not superstitious. I might be a fool, a failure, a bad actor, but I refuse to be a sucker. Again. “I’m not going to see him, and that’s final,” I tell her.

She escalates her attack. She mentions Rabbi Nissim every three to four hours, as if he were a Tylenol she must keep dispensing. “My hairdresser,” she says, “is well acquainted with a dentist assistant, whose sister went to see the Rabbi. Guess what happened? Two days later, this dental assistant, who’s not half as clever as you are, met the man of her dreams, and now, she’s married and owns Israel’s second-largest falafel chain, tfoo, tfoo, tfoo.”

When my mom relays an especially positive anecdote, about anything, she dry-spits three times to make sure she doesn’t jinx anyone.

“My pharmacist is friends with a florist whose cousin went to school with Rabbi Nissim. She says that even then, as a boy, the Rabbi was a prophet. When he was thirteen, he told her that she was going to break her arm, and three days later, she broke her foot!” My mother exclaims in triumph.

And when I’m desperately trying to sleep off my jetlag, “Listen! Listen! That’s him!” She cranks up the volume on her little radio. Thump! Thump! Her neighbors, a sweet elderly couple, bang on the wall in protest. She wheels to the thumps, yelling: “Be quiet! Rabbi Nissim is talking!”

Fed up with her shenanigans, I scream, “WILL YOU STOP? I’m not going to see him. Never, ever, ever!”

She turns to me, blinking back tears. Uh-oh. The big guns are out. I shouldn’t have yelled at her. “I’m sorry Mom. Oh, no, no… don’t cry.”

She sniffles. “I just want you to be happy. Is that so bad?” she asks in a small, broken voice, tears glistening down her cheeks. “For me, Tali. For me. Plea-se…”

Like I said, she’s a guilt specialist. I have no choice, but to surrender.

Normally, we meet with the miracle worker du jour after an enormous breakfast, but to see Rabbi Nissim, we take a taxi late one night after she makes me an enormous dinner. Apparently, the Rabbi only meets with people after he finishes recording his radio show.

At 9:30pm, we’re among the first to arrive at Beth-El Synagogue—a humble Sephardic temple. Three orthodox, pubescent girls mill by the entrance in long skirts, ponytails and shiny Mary-Janes. Mom—a General addressing her troops—asks them, “Is Rabbi Nissim expected here?”

“Yes!” they say in unison.

“My daughter is unmarried,” Mom says as if my singlehood is cancer.

The wholesome triplets consider me with pity. Like most Jewish orthodox girls, they’ll undoubtedly marry by the time they’re twenty. “God willing, the Rabbi will help her,” one of them says.

A pale young woman with braces appears behind us. “I’ve been to see the Rabbi three times. He changed my life, God bless him. He has changed my life,” she repeats, spellbound, then slinks out, into the darkness, like a ghost. Mom turns to me victoriously.

“They’re brainwashed,” I whisper to her. “It’s a cult.”

“For once in your life, think positive!” My mother, Queen of Negativity, says and takes a prayer book from one shelf. She situates herself on a bench by the door. I plop down next to her and whip out my phone.

“No phones!”

“What do you expect me to do here?” She reads her Bible, flagrantly ignoring me. I lower the phone with a sigh.

A flimsy partition divides the men’s section from the women’s. We, the women, are relegated to the back of the synagogue, far from the dais and holy ark, where Bible scrolls are nestled. The walls are unadorned except for a long list of names engraved in gold. Donors, I think. No, dead people. Members of this congregation, who perished on the battlefield or on a bus that was blown up. I think of the names engraved into the sidewalk on Hollywood Boulevard. It feels wrong to be familiar with names of movie stars but know nothing about these victims of war and terror.

We wait. We wait some more. We take turns going to the bathroom. Women trickle in.

Young, elderly, in between. Orthodox and secular. Some wear a head-covering—scarves, hats or wigs—others wear lipstick and jeans. Some are in wheelchairs or use walkers, a handful carry babies. “We were here before you,” my mom says to each newcomer until the trickle turns into a torrent, and she can no longer ensure they keep track.

At 11pm, there’s still no sign of the Rabbi. The crowd has tripled. The synagogue is hot, loud and suffocating. The women fill the benches and spill into the center aisle and narrow hallway by the entrance where they sit on the marble floor. Through the flimsy divider, I can see that the men’s section is almost empty. I’m angry with these women, who choose a hard floor over a man’s seat, and I’m angry with this Rabbi who’s making us wait as if he were the Messiah. Sensing my dismay, Mom whips a banana from her bag and offers it to me.

“I don’t want a banana. I want to go home and sleep.”

“Be patient,” she says and tries to stick the banana in my hand. I push the fruit in protest. Upset, she continues, “Maybe the Rabbi will get you out of that nuthouse, that Hollywood.”

“I’m an actor. Actors live in Hollywood.”

“You’re a waitress.”

“A maître-d’! And by the way, I’m on a management track.”

“When will you stop kidding yourself?”

“It’s called paying your dues. I’m following my dreams.”

“Dreams! You can’t pay rent on dreams. You can’t have children on dreams. Have a banana.”

“I DON’T WANT A BANANA!” I rise, ready to flee. But then, a round-faced woman, in a modest brownish dress and matching beret, appears, breaming with purpose. “Hello everyone, I’m Judith,” she calls out.

My mother shoots me a glance. I sit back down. Judith continues, “The Rabbi thanks you for waiting. He just left the studio. He’ll be here by midnight, God willing.”

An excited murmur cuts the stale air. Judith proceeds to hand out Books of Psalm. As she does, the women tell her their stories: an elderly woman bemoans her paralyzing arthritis; a woman with dark circles under her eyes worries about her enlisted son; a weeping woman suspects her husband is unfaithful. Judith listens to the stories, offering soothing words. I lean against my mother’s shoulder and close my eyes.

A Hassidic melody awakens me. I must be having a nightmare. But no. I see Judith answering her phone. Then she announces, “The Rabbi has arrived!”

Elvis is in the building. The women turn to the entrance. I follow their gaze, as Rabbi Nissim walks in. He has the full beard and peyos that characterize orthodox men, but he’s astonishingly handsome: Tall, buff, brownish-reddish hair, straight nose, blue-blue-blue eyes. He struts to the stage and climbs up, commanding: “Psalm 121.”

We open our books as he reads the song in a clear voice, swaying as he does. “I will lift up mine eyes unto the mountains: from whence shall my help come?…”

I grin in delight. “He’s too good looking! It’s distracting,” my mother snaps, trying to kill my joy. I raise my phone to take a picture of this vision of manhood. Mother smacks my hand down.

The Rabbi continues in a hypnotizing lilt, so charismatic, he could be playing with the Stones. He delves deeper and deeper into the Psalm, a conduit of light and energy, his swaying more frequent and pronounced. “Names!” He shouts in ecstasy.

A pale woman springs up, crying, “Yaakov, son of Efrim!”

“Yaakov, son of Efrim!” The Rabbi repeats and adds, “Bless him!”

A frail-looking matron, supported by two young women, rises, croaking, “Daniel, son of Meir!”

The Rabbi looks up, conversing with the Almighty: “Daniel, son of Meir! Bless him!”

One by one the women call out the names of loved ones, and the Rabbi repeats each name and pleads with God on their behalf. Occasionally, the women burst into tears as the Rabbi’s blessing rises to the heavens.

It’s impossible not to be moved. I wipe my moist eyes. My mother mouths: “I told you!” Then, she rises and cries out, “Tali, daughter of Miriam!”

“Tali, daughter of Miriam! Bless her!” The Rabbi commands.

I don’t know if it’s his booming voice, the energy in the room, or if an otherworldly presence is among us, but a tingling sensation travels from my toes to the crown of my head. I feel cleansed, transported. Shaken. Did my mother get it right this time? Is Rabbi Nissim, the real thing—a miracle worker?

The Rabbi’s ritual is magical, ancient, primitive. It goes on and on, minutes melting in the Rabbi’s heat. Finally, he steps off the dais, exhausted but glowing. Judith brings him a glass of water. He walks away, toward the entrance, then disappears into one room.

“Wow.” I turn to my mom. “Wow.”

“You have to talk to him. Quick!” Mom charges to Judith. I trail reluctantly. “We were here first,” she says. “My daughter flew from America to see Rabbi Nissim.”

Judith studies me. “Did you come from America to see the Rabbi?”

“Well…” I mumble noncommittally.

“She lives in Hollywood, alone, like a homeless person! Thirty-three. Unmarried.”

Judith acknowledges my dire condition with a nod. “The Rabbi needs a moment to collect himself. The work of the righteous is never done.”

Mom and I wait outside the Rabbi’s office. Right outside. Our noses almost touching his white door. The women line up behind us.

Judith approaches with a woman who’s connected to a portable oxygen tank. My mom stares the woman down, ready to ramble. Judith tells her in a conciliatory tone, “A sick woman…” Mom, exercising unusual restraint, steps back. The ailing woman shuffles into the Rabbi’s office and closes the door.

Two minutes later, the door opens. Apparently, the Rabbi works his magic quickly. Ailing woman emerges, wiping tears. “Oy, oy… What a man… A saint!”

Judith turns to me. “You’re up.”

I freeze. Do I really want to be a movie star? Am I ready to get married? What if Rabbi Nissim is about to change my life? What if he fixes me?

“What are you waiting for?” My mom nudges me into his office and says, “Tell him to touch your head!”

Judith closes the door behind me.

The corners of the room are dark. The Rabbi is seated in a pool of light, bent over a Bible, which is open on a small table in front of him. A massive collection of books, most with tattered spines, lines the walls.

“Come in, sit down,” he says without looking up. I join him at the table. “Should I read you from the Torah?”

I stare at him, but he keeps his eyes on the holy book. Orthodox men are forbidden to gaze into the eyes of a woman who’s not their wife, daughter or mother. I’ve always felt it was a sexist, discriminatory practice. I decide to level with the Rabbi. “I’m only here because of my mother.”

“Oh?”

“I’m 33, unmarried and a struggling actor in Los Angeles. She thinks you can ‘fix’ me.”

Rabbi Nissim’s blue-blue-blue eyes meet mine. Why is he looking at me? I wonder if I hurt his feelings with my bad attitude.

“Do you live in Los Angeles?” he asks.

“I visit Israel once or twice a year,” I tell him, trying to make my desertion of mother and motherland sound palatable.

“I used to live on Hayworth Street in West Hollywood.”

“You’re kidding.”

“So… What was the last movie you saw?”

“You mean, like, in a movie theater?”

“Anywhere.”

“Ah. Well, I watched an animated film on the plane.”

“Disney?”

I nod.

“And Meg Ryan? How’s she?”

“Huh?”

“When Harry Met Sally, You’ve Got Mail…” he says, indignant.

“Ah, she’s fine, I guess.”

“A Hollywood actress, and you don’t know your last Meg Ryan movie?” he shouts, incredulous.

“She pretty much left the business.”

“Left Hollywood? Meg…?” He studies me, devastated. A knock on the door interrupts us. He looks down, burying his gaze in his book. The door opens, and Judith pokes her head in. “We have a long line, Rabbi. You’ll be here all night.”

“Thank you, Judith. We’re almost done.” Judith retreats and closes the door. He looks up at me. “Quick. Tell me about this animated movie you watched.”

“Ah, it’s about a queen in an icy kingdom who has a complicated relationship with her sister… Aren’t you supposed to bless me or something?”

“What’s it called?”

“The movie? Frozen.”

“Frozen… I saw the billboard, I think.” He pauses, thoughtful. “Before I moved to the west coast and lived on Hayworth, I headlined a revival of Hair, the musical, in Chicago.”

“You were an actor?”

“And what a tenor I had. They came to see me from the William Morris Agency. What movies have you been in?”

I dread that question. My credits are pathetic. I tell him, “Apparently, you’ve been disconnected from any form of secular entertainment for, like, decades, but if you had Netflix, you would have recognized me from the cult classic, “Sorority House Vampire V: In the Beginning.”

“A prequel!”

“An independent. I play a sorority girl who turns into a vampire.”

“I used to love vampire movies.”

“We shot in Palmdale, in the desert. Nonunion. $125 a day… Who am I kidding, Rabbi? My mother’s right. I can barely call myself an actor.”

“Mmmm… I take it you’ve never met Tim Robbins. Wonderful that Tim.”

“My mother said you would help me!”

“I thought you didn’t need my help.”

“I’ve been taking acting classes for ten years. I drive a crappy car, have a ton of credit card debt and basically zero credits. Of course, I need your help!”

“Harry Potter was the last movie I saw. That was the year I found my faith. I left Hollywood. I left my girlfriend. Now, I have a wife and seven children… Do you know my show is the #1 talk radio show in the Orthodox market?”

“Which is huge, I’m sure.”

An urgent knock. He quickly looks at his book again. Judith storms in, face flushed, lips pursed. “We have a line, Rabbi! The women. The women are waiting. The women are waiting, and they’re sick!”

“I’ll be with them soon. Please. Leave us.”

Judith gives me the stink eye and steps out, closing the door.

The Rabbi meets my gaze again. “You know what I do? I listen to suffering people. Every day, I ask the Almighty, why did He put us on this earth to suffer?”

“What does He say?”

“I’m unworthy of His reply.” He looks at me, deeply sad.

“But you’re a holy man, a prophet…”

“I had it all: screentests for Paramount, William Morris ringing nonstop, and the reviews… A young Brando, they said. A huge talent, they called me.”

“I wouldn’t know. No one’s calling me, ‘a huge talent.’”

“You don’t believe me.”

“What?”

“You don’t believe I was good. That I could have been a star.”

I try to sound convincing. “Sure, I do.”

He frowns, shaking his head. Then he, well, he sings: “She asks me why, I’m just a hairy guy, I’m hairy noon and night, Hair that’s a fright, I’m hairy high and low, Don’t ask me why, Don’t know…” I gaze in amazement as he rises and reaches for my hand. He pulls me to him then spins me around, singing, “It’s not for lack of bread, Like the Grateful Dead, Darling!” He releases me. Dizzy, ecstatic and deeply concerned, I watch as he points to his full beard to illustrate the song’s lyrics… “Gimme head with hair, Long beautiful hair, Shining, gleaming, Streaming, flaxen, waxen…” Voice searing, he climbs on the chair. “Give me down to there hair, Shoulder length or longer, Here baby, there Mama, Everywhere Daddy Daddy!!” The chair teeters, about to give.

I run over, steady it. Three loud knocks. The door flies open! Judith sticks her head in and cries, “Oy Vey… Rabbi! You’re forgetting yourself!” He freezes. Judith exits and slams the door.

He climbs down, defeated. “I am nothing,” he tells me.

“That’s not true… You’re the #1 talk show host on orthodox radio… You’re a miracle worker. When you said my name, when you asked God to bless me, I got chills…”

“You did?” He smiles, but his eyes are still sad.

I feel his yearning. “You really miss it, don’t you?”

“No, I’m happy. A happy man,” he says. “What about you? What do you want?”

“I want to, you know, do what I love.”

“Only you can make that happen.”

“I want, I want to know it’s okay that I left.”

“Okay with whom?”

“My mother, I guess. She wants me near her. She suffers when I’m away.”

“Maybe you suffer, too.”

A terrible thought occurs to me. “What if I don’t make it? What if all this suffering is for nothing?”

“Our dreams come from God. There’s nothing higher than pursuing them.”

“You didn’t.”

“My dreams changed. Sometimes, when God gives you what you want too quickly, too easily, you think you don’t want it anymore.”

Ah. It occurs to me that that’s worse than not getting what you want, but I just say, “I’m glad we met.” And then, “My mom said to ask you to touch my head.”

“Do you want me to?”

I shrug and walk to the door. He calls after me, “Not so fast, Sorority House. Show me your best vampire.”

I turn to him and expose my canines with a growl… We giggle.

I open the door and leave.

In the hall, Judith gives me a death stare and quickly escorts an elderly woman into the Rabbi’s office.

Mom whisks me away, giddy. “What an honor,” she gushes. “Who gets an extra special long meeting with the Rabbi? My daughter! My Tali! So? What did he say? Did he touch your head? Did he bless you?”

I wrap my arms around my impossible mother, grateful for her. “It was perfect, Mom,” I tell her. She blinks back tears of joy, as if a miracle had happened, as if all our prayers will be answered. And maybe they will.

What's Your Reaction?

Micky Levy is a writer and filmmaker. She was born in Israel to cinephile parents and grew up watching movies and writing poetry and short stories in Hebrew. After arriving in Los Angeles by herself at the age of 17, Micky caught the eye of Alison Eastwood and Warner Bros. with her script RAILS & TIES. The film starred Kevin Bacon and Marcia Gay Harden and played in Telluride and TIFF, among other festivals of note. Micky has completed several book adaptations, including AMISH GRACE for which she received a Humanitas Prize nomination. She wrote, produced and directed the award-winning shorts PAGE’S GREAT AND GRAND ESCAPE and UNION. She is a Film Independent Screenwriting Lab Fellow, a Tony Cox Showtime Top Ten finalist, and her script SHE’S NOT GONE is featured on Wscripted's Annual Cannes Screenplay List. "Miracle Worker", published with Green Golem, is her first short story in English. She is also working on a picture book and her first novel.

I so enjoyed this short story. Found it truly relatable and reassuring. Looking forward to the sequel perhaps?

I like the way you contrasted populist culture with that of your family value systems and the way you injected notions of realism into the narrative. The work rings true as a Jewish narrative and highlights some of the serious intergenerational tensions in Jewish life. What struck me the most about this work is that it is contemporary because the popular cultural references you make are known to my generation namely GEN X. So this piece of work is more than just a commentary about how family and religious values intersect, but also reflective of a specific time in modern global history. Some may say that your story describes an East versus West conflict zone, but I believe that this piece of work has significance within a historical realm and should be preserved and revisited in a century when the truth of the nature of this apparent conflict will finally surface. Thank you for describing our current struggles.