Mansion over the Town Fields

David Shrayer-Petrov (z”l), writer, medical scientist, and former refusenik activist,…

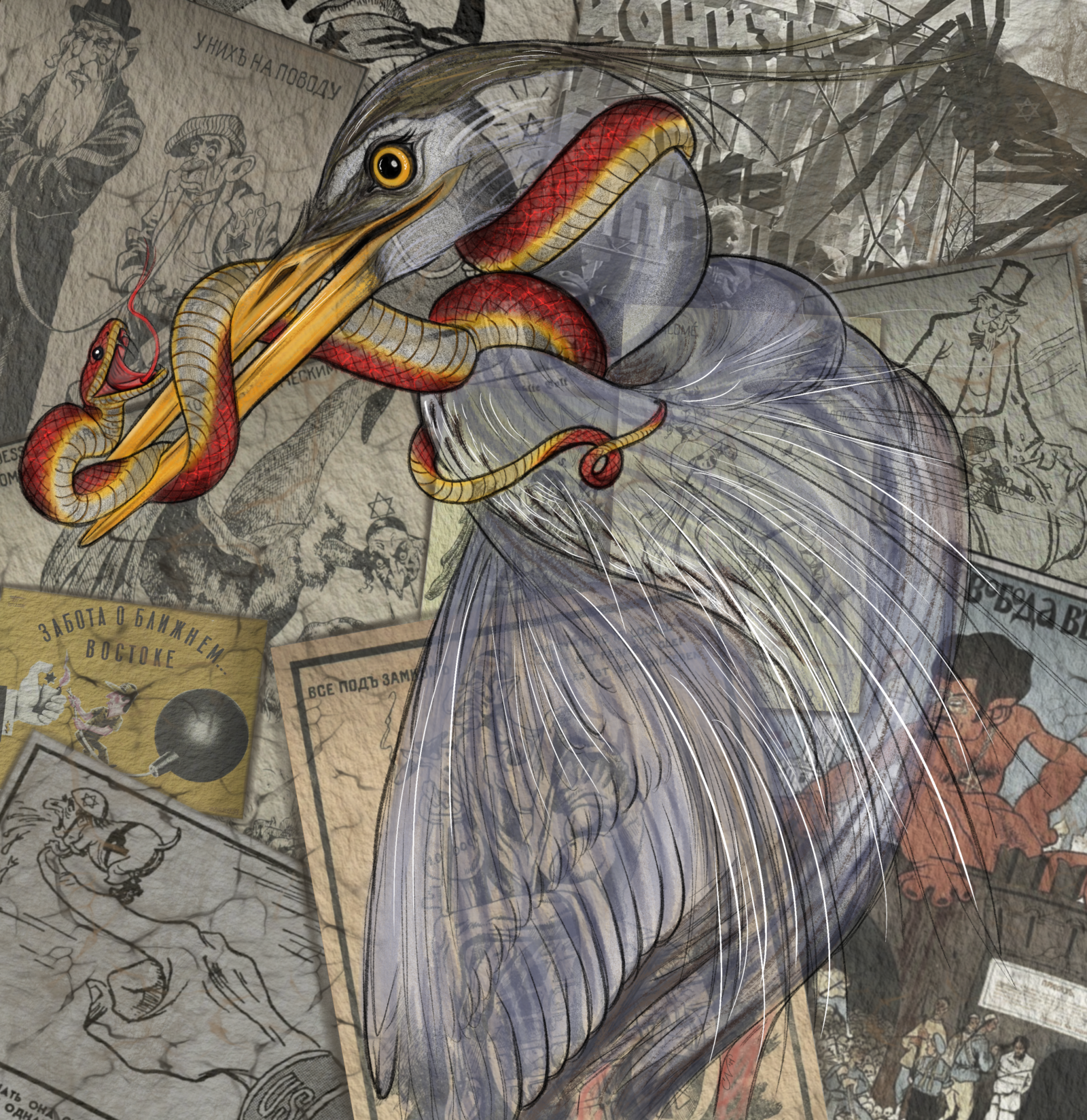

They had been out to see a movie in Coolidge Corner. Afterwards they went to a pizza parlor next door to the movie theater. They weren’t ready to part. Unhurriedly, they walked in the direction of her house, which stood on a hill overlooking the town fields. The playfields were in a large public park, and the grass there looked evergreen even in winter, because the sun often visited the park and warmed the ground, helping the grass to grow and preserving it until the next spring. Behind the park fence there was a conservation area with a pond stocked with types of fish native to the Northeast. Around the pond one could observe different birds—birds one didn’t encounter very often in urban areas. For instance, the blue heron.

He sometimes said to her: “Your eyes are the color of this blue heron. And you have long legs.”

“Do I also need to stand for hours on one leg?” she would reply with a mock feistiness. He then kissed her on the warm lips.

It took them a while to say goodbye in front of the mansion where she lived with her parents. Her older brother used to live there, too. But three years ago he was accepted to Berkeley, and now he only came home from California twice a year, for Thanksgiving and Passover. He loved his university life, where quickly he became engrossed in experimental biology research, and even if he came back East to spend the last week of August at the family cottage on Cape Cod, he wouldn’t stay in Brookline for Rosh Hashanah, which often fell in September. Theirs was a Jewish nontraditional home, where everything was allowed, except you couldn’t forget your origins and you had to know the main tenets of Jewish history. And one more thing: boys weren’t allowed to stay over. Her male guests were expected to leave no later than midnight. Those were the house rules. Her father, a senior bank executive, followed them religiously.

Her name was Margaret, Margo, Marge. She had dark chestnut hair, smooth cheek bones, blue eyes, bright lips; an iridescent smile flowed in and out of her mouth—slightly ajar like that of a marathon runner. And she had long shapely legs. In the fall Margaret liked to go around in a black pea coat. It was now October. She was a student at Boston Conservatory and dreamed of becoming a concert pianist.

His name was Christopher; Chris. In moments of tenderness she called him Christy. Friends had a nickname for him: “the Skald.” He wrote poetry. Red curls fell down his shoulders; under T-shirts or sweaters, his shoulder muscles bulged, taut like sailboat lines. When they spoke about politics, Margaret would chuckle mysteriously, as though she took for a given the many amusing imperfections of human society, even if this miniature society was just the two of them. Chris openly laughed at liberals and conservatives alike, not even in derision, but because he most valued in humans and humanity those qualities that he found unique to the point of ridiculousness. Politicians’ laughable or extravagant qualities would become more obvious on the TV screen—in speeches and interviews. Chris was especially fond of an aging, athletic Black congressman who always resorted to combinations of apples and oranges while discussing economics and politics.

Chris couldn’t stand—and generally avoided—self-righteous persons who go to bed on time, wake up with the alarm clock, pay bills when they are due, and agonize over matters of widely accepted morality. Chris was unfussy about living conditions. His weathered barn jacket had become a part of his whole being. Hand-printed on the back of his barn jacket was a quote from the dissident bard Leonard Cohen: “First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin.”

Chris was of working-class background. For many years his father, whose parents immigrated from Ireland and from Norway, and his mother, who as a child was brought to America from postwar Poland, had been breaking their backs—literally, in keeping with this staid metaphor of hard physical labor. Chris’s father had spent twenty years either lying under cars in the shop or darting between cars at the gas pump. Finally, by the time they had reached their forties, Chris’s parents had saved enough to put down ten percent toward the purchase of a Shell gas station in their neighborhood, which was being offered for sale at a moderate price. His father entered the entrepreneurial class, but this in no way changed his lifestyle. He still worked on cars, except now he spent less time at the fuel dispensers, inserting nozzles into gas tanks, collecting cash from the customers or running credit cards through the machine. Another employee, a college dropout, now handled these tasks; he had studied literature, took pride in Pushkin’s African roots and liked to quote the line “Under the sky of Africa mine.…” Despite the grinding monthly payments they owed the bank for the gas station, Chris’s father sent his son to Emmanuel College, hoping that his ancestors would look gladly at the first lawyer in their lineage.

The film Margaret and Chris had seen that evening was French, a traditional family drama. Woven into the story, which was set during the German occupation of Paris, were destinies of French Jews. The heroine of the film had lived through the war and occupation. Although married to a prominent banker, a Catholic and an heir to an old French aristocratic family, she was Jewish by birth. Long before the war she had concealed her origins, knowing all too well that her fiancé’s family wasn’t too fond of Jews. By carefully practicing mimicry as a French woman and wife of a French Catholic banker, she was able to avoid deportation and survived. All would have been well, had a little animal called conscience not awakened by the end of her life—somewhere in the left side of her chest. This little animal of a conscience brought to mind the myth of a Spartan boy, who put a little fox under his shirt, and then the little fox bit through the boy’s skin and ate through his flesh right at the heart, causing the boy’s terrible torments and killing him. The remorse—the moral suffering of the banker’s wife—was no less terrible than the Spartan boy’s physical pain. She had been enduring it and suffering her entire life, but she didn’t want to die a malefactor, choosing instead to confess her lifelong lie to her son and grandchildren.

Margaret and Chris walked slowly, as if each of them was reflecting on the film, recalling the most burning shots and viewing them again. The odd part was that as they watched the film together, Margaret was several times on the verge of leaving, so repulsed she was by the ruminations of the banker’s old wife. Hadn’t the war and occupation been long over? Did the cursed Jewish question still matter somehow, Margaret mused. Probably here, in America, it didn’t matter, but in France it did. And still does. Otherwise, why would the banker’s wife be so surreptitious in opening her secret to her son and grandchildren? Was her secret—being a Jewess—really so terrible? Margaret caught herself thinking that she wasn’t sure whether she should discuss the Jewish question with Chris. There was a chance he wouldn’t understand her own doubts and ruminations, so far many Americans were from these problems. To them these weren’t problems at all. And yet, perhaps she should discuss the subject with him, she wondered. Unremitted, like discrete matter, the history of humankind keeps returning to its eternal stories. And if so, aren’t there always traces of the past in the present?

As if reading her thoughts, Chris said: “Some sort of a demented French lady. Here in the US we don’t have such old ladies.”

“Because here it doesn’t matter who you are—Jew, Catholic, Protestant,” Margaret said with feeling. “Tell me, Christy, does it matter to you that I’m Jewish?”

“The important thing is that we love each other.”

He drew her close and they started kissing.

They walked, then stopped again to kiss, then walked on before they finally reached Margaret’s house. Lights were on outside the front door. On the third floor, in her father’s study, a green lamp shone like a Turkish moon. He never went to bed before Margaret got home.

Margaret had met Chris less than three months ago. He came with college friends to a recital by Boston Conservatory students. During the intermission, without saying anything to his friends, he went backstage, found Margaret and asked her to have a drink after the concert. That’s when it all started. They had been spending a lot of time together. And yet, despite her invitations, Chris never set foot in her house.

“Why not? Are you shy?” Margaret asked him.

“Do I seem shy to you?” he answered, laughing. “I love the area near the town fields. It’s so open, spacious. What do we need inside your mansion?”

Margaret wondered why Chris didn’t want to come inside. Was he embarrassed? Was something bothering him? And if not, why does he refuse?

One time he invited Margaret over to his house in the middle of the day. Chris’s family lived on the Brookline-Boston line, where the T tracks and the routes of the city buses converged, an area always overcrowded by heavy trucks, taxi cabs and delivery vehicles. It was a fiefdom of gas stations, auto parts stores and collision repair shops, as well as new and used car dealerships. From morning until evening this area was bustling with hoots, rattles, honks, whistles, and bells. Chris loved these street sounds and noises. Amid them he was at home the way a farmer is at home in a cornfield, amid the swoosh of husks and rustle of stalks. Chris’s father was working at his gas station. His mother had gone to Worcester to visit her older sister. Margaret and Chris were completely alone. Nobody stood in the way of their love. She loved him with passion, Chris could see and feel it. No other lips but hers kissed him with such desire; no other lips could imbibe every tiny cell of his body. And never before had she yearned for anybody this way.

And even after this, Chris wouldn’t go inside her house. Why? She asked herself, and, burdened by her intuition, she no longer insisted.

The exact same thing happened at her family’s Cape Cod place. He adamantly refused to spend time inside their cottage, and wouldn’t even want to stay over when her parents went back to Boston earlier to see a play or attend a social event. Twice Chris came down to the Cape on a Saturday or a Sunday. He called her on her cell phone. They drove to the beach, swam and cavorted like carefree children while it was still warm. The second time, at the end of September, they just strolled on the beach. They walked for a very long time before they found themselves outside a large waterfront estate surrounded by a mauve stone wall, behind which there stood a castle with a tower, capped with a parody of an emerald cone.

“Yeah, these ones have walled themselves off from the world,” Chris pressed out and spat through the teeth.

Usually, before having breakfast and taking the T to the music conservatory, Margaret would pull on navy exercise pants and a matching navy top with a white trim and head to the park to do her stretches and then run. At this early hour the main field, still bright green even though it was the middle of October, would be the domain of dogs who chased each other while their owners (would it be more appropriate to call them nannies, guardians, protectors, trainers—anything but owners?) stood there, undone and unwanted leashes in their hands, mirthfully observing their wards and occupying themselves with soulful conversations on dog-related subjects. On that particular early morning everything was the same, and yet something new had sprouted up. Strewn across the green field, which was still dewy from the night, were various uncharacteristic objects: sleeping bags, blankets, shopping carts, large thermoses, folding tables and chairs, packages of bottled water and many other things usually found at a tourist campsite, or perhaps in a refugee camp. And she could see drowsy faces of the inhabitants of this encampment peering out of the sleeping bags and from under the blankets and covers. At first the thought flashed through Margaret’s mind that this was an athletic competition, a temporary station, perhaps a fall outdoor training of one sort or another. But she quickly rejected the thought, because the vagrant camp was a scene of utter chaos. Even dogs, usually romping around on the field, now wandered in disbelief amid the alien objects and strange people.

Margaret had no time to investigate the origins of the gathering, so unusual for their town park and fields. She finished her run and did some more stretching exercises beside the bench erected there a few years ago with the funds donated by her father, to which a brass plaque with his name attested. She hurried back home to shower and change, have breakfast and catch the T to a piano lesson with a Russian lady who had once been a famous performer.

It was Friday. Chris had some urgent work and couldn’t see Margaret, and the following morning she and her parents left for Cape Cod. Her father drove their Mercedes, discussing something with her mother. Even though he spoke in a quiet staccato, so characteristic of his personality, from the back seat Margaret could hear scraps of his phrases—something about a movement against the banking industry, something under the main slogan “Occupy Wall Street.” She wasn’t really focusing on her parents’ exchange, preoccupied with thoughts about the new piano piece she needed to master by the following week. She liked, before sitting at the piano, to read the notes with her eyes only, hearing the music from within. She tried to figure things out by herself. This was true of her studies, her family, her relationship with Chris. Margaret had one very close girlfriend, Abby, with whom she could talk about anything, including her love for Chris. But Abby had gone to New York for a couple of days…

A relaxing weekend routine awaited them at the Cape: walks by the ocean, choosing a restaurant for lunch, getting together with friends who had houses within a short drive from their cottage. They had lunch at the Yacht Club dining room and then drove back to the cottage. Margaret sat at the piano and practiced for a while, still reluctant to join her parents on a visit to a friends’ house. Eventually she agreed, but not after her father looked at her, his eyes the misty color of morning sky, and said, “Please come with us, sweetheart. We hardly see each other during the week.”

Later Margaret regretted her acquiescence. She would have been better off staying behind and lying in the hammock, reading and following the convoluted storyline in Bashevis Singer’s Enemies: A Love Story. This would have been more fun than having to endure a long discussion about some protesters, who had flooded the area of lower Manhattan around Wall Street. During cocktails at their friends’ house, one of the guests brought up the tent city, which had sprouted in the vicinity of Wall Street, and also spoke of the crowd’s anarchic hatred of banks and bankers. From the TV screen, the audacious slogan “Occupy Wall Street” kept sounding again and again. Margaret thought that the ironic tone, with which her parents and their hosts repeated the slogan, masked their unease.

What’s all the commotion about? Margaret was thinking. Those leftists; yet another round of demanding the impossible. Who would support them? But then she doubted her own judgment as she recalled the recent morning at the park, sleeping bags and tents with their peculiar inhabitants. Margaret didn’t want to give the impression that the discussion of a crowd armed with protest slogans concerned her directly. Did it concern her directly because of Chris? And where was he, anyway? She missed him. What if their love suddenly came to an end—love yielding to indifference? She started wondering if this transition from love to indifference wasn’t somehow connected with her morning run and the alien tents raised on the grounds of the town fields. Shaking off her thoughts, she glanced at the TV screen. The camera showed a close-up of a small group of protesters. Fluttering over their heads was a banner with the words “Down with Jewish Bankers.” A heavy silence now hung in the living room. The host, himself a financier, pushed aside his martini glass and sprang up from his chair.

“I can’t bear watching this filth,” he said and turned off the TV.

“I just hope this filth doesn’t turn into something like the marches of Nazi stormtroopers,” Margaret’s father said. “They, too, had started by parading their socialist-anarchist views.” When her father’s eyes met Margaret’s, she noticed that they had turned from sky blue to the dark color of ocean before the storm.

After they got back home to Brookline, Margaret’s father went jogging in the park; he liked to stretch out his limbs after sitting in the car. And later, Margaret could tell from his alarmed face that he had seen the tent encampment.

A week went by. The local news channels showed groups of protesters moving across downtown Boston and carrying solidarity banners, “We Support Occupy Wall Street,” and also banners with the words “Occupy Boston.” Margaret had invented some perfectly natural excuses not to go running in the park. Chris hadn’t called for a whole week. And Margaret had also come up with an acceptable explanation: he must be overwhelmed with papers and deadlines.

Late Friday night she drove to the Cape with her parents. They hit the usual weekend traffic. Margaret stared at the flashing masts of tall roadside pines and thought about Chris. Why hadn’t he called? Things at school? What if.…? Margaret mulled over possible reasons, some logical and others utterly senseless and conflicting, behind his silence. She couldn’t share any of this with her mother. In the past she might have done so, as she had previously told her mother about the boys she was dating. But this time she was embarrassed. Almost as though her fear of opening up to her family was somehow linked to the park and town fields, which their mansion overlooked, and also to the news coverage of the people who had been openly protesting banks and bankers. Was she afraid she might see Chris among the protestors?

As usual, they returned to Brookline on Sunday toward the evening. Before the latest weekend at Cape Cod, Margaret had resolved to wait until the strange tourist encampment, which looked more like a demesne of vagabonds, would disappear without a trace. She had now recognized a common thread among the vagabonds at the town fields, the crowd in Manhattan calling for the occupation of Wall Street, and the local news reports of protestors who had taken over Dewey Square in downtown Boston.

Something akin to clairvoyance, which one experiences during critical turns of one’s life story, pushed her to return to the park the following morning, even though her previous visit had left her with a muddy aftertaste. At about seven in the morning Margaret left her house and walked down the sloping hill studded with old oak trees, their feet sunken under piles of acorns. The acorns made her think of little people dressed in funny hats tilted to the side, and she chuckled at her own ability to find distraction in something so simple and silly.

Margaret came down the slope and ran toward the main field. The encampment was gone. Almost entirely gone. Only a couple of tents remained. Their inhabitants must have slept through reveille and were hurriedly dismantling and folding their tents, deflating and rolling up the mattresses, stuffing their camping gear into backpacks. Margaret was familiar with the life of campers. In high school, especially at a summer Jewish camp in New Hampshire, she had participated in hikes to low wooded mountains, followed by overnight camping at a lake waterfront. She understood the inner workings of the summer campers’ easygoing life: field cooking, lake swimming, sing-alongs by the campfire, trading glances with boys, and rushed, furtive kissing behind the shields of ancient tree trunks. When she saw the last remains of the departing group of campers, she felt relieved. Her premonitions must have all been wrong, and this had nothing to do with her Chris. She was about to resume her morning run when she found herself face to face with a short fellow wearing a wide-brimmed leather hat and gaudy cowboy boots. The fellow looked familiar; she might have seen him at the bar in Coolidge Corner, where she and Chris had gone for drinks a few times. The fellow was stuffing a metallic blue tent into the bag, shaking his head so that the copper crescents of his earrings jingled like a gypsy band from an old movie.

“You haven’t seen Chris, have you?” Margaret suddenly asked the fellow.

“You mean, the Skald?” the fellow replied.

“Yes, the Skald.”

“Sure I have. He’s one of our protest leaders. He and the main group went to Dewey Square. That’s where they are now.”

Margaret dragged her cotton ball feet back home. She quickly changed, ran out and got into a cab in front of the nearby Holiday Inn. “Dewey Square, please hurry,” she told the driver, who had a Russian name. He just grinned back.

Twenty minutes later Margaret jumped out of the cab and saw a tent city right before her eyes. Tents had been put up sloppily; here and there, dirty mattresses jutted out. Overflowing trash bins stood akimbo. There were buckets filled with junk. Scraps of newspapers and posters were scattered on the ground. Primitive cooking stoves emitted smoke, and she could also see sundry objects of what could be imagined as a nomadic encampment, a town under siege or a community of hobos.

Flapping in the wind were hastily and crudely painted banners with the most revolutionary of demands addressed to the authorities, to financial magnates, to big corporations and various other powerful offices and institutions—slogans made on behalf of the world brotherhood of people brought to the point of desperation. Nobody paid attention to Margaret as she searched for Chris in the crowd.

“Let’s go to Park Plaza… Israeli Consulate,” she heard one of the protestors shout. Two new banners soared above the crowd: “Israel Must Go” and “Free Palestine.” Scanning the crowd with his eyes, Chris the Skald walked ahead of a group of protestors. He spotted his girlfriend but didn’t stop. He was leading the protesters in the direction of a police cordon, holding one side of a large banner with the words “Occupy Boston” painted on it. Overpowering the voices of his comrades, he waved with his free hand and called out:

“Margo, over here. Come with us.”

“Israel Must Go,” echoed the crowd. “Israel Must Go. Israel Must Go.”

“Chris, no. I can’t!” Margaret shouted, speaking more to herself than to the man she loved. “I’ll never go with you. Israel will stand forever.”

Copyright © 2024 by the Estate of David Shrayer-Petrov and by Maxim D. Shrayer

David Shrayer-Petrov (z”l), writer, medical scientist, and former refusenik activist, was born in Leningrad (St. Petersburg) in 1936, immigrated to the United States in 1987, and died in Boston on June 9th, 2024. He published twenty-six books of poetry, fiction and nonfiction in his native Russian. Shrayer-Petrov’s books of fiction in English include collections of stories such as Jonah and Sarah, Autumn in Yalta, Dinner with Stalin and Other Stories, and the novel Doctor Levitin.

Maxim D. Shrayer, the author’s son, is a professor at Boston College and a bilingual author and translator. Shrayer is the author, most recently, of Kinship, a poetry collection.

Illustration by Charis Nwaozuzu. Charis Nwaozuzu is a tattoo artist out of Oklahoma. She is a Jewish member of the Cherokee Nation. She believes that storytelling through art is deeply rooted in both of her cultures, and is excited to be passing that tradition down to the next generation as well.

What's Your Reaction?

David Shrayer-Petrov (z”l), writer, medical scientist, and former refusenik activist, was born in Leningrad (St. Petersburg) in 1936, immigrated to the United States in 1987, and died in Boston on June 9th, 2024. He published twenty-six books of poetry, fiction and nonfiction in his native Russian. Shrayer-Petrov’s books of fiction in English include collections of stories such as Jonah and Sarah, Autumn in Yalta, Dinner with Stalin and Other Stories, and the novel Doctor Levitin.